How Digital Technology Changed Presidential Politics

Would Lincoln have been elected in the age of Facebook? Would Woodward and Bernstein have been credited with toppling the Nixon administration if WikiLeaks had been a thing? How would Reagan have navigated the Cold War if he’d had to deal with cyberterrorism?

Would Lincoln have been elected in the age of Facebook? Would Woodward and Bernstein have been credited with toppling the Nixon administration if WikiLeaks had been a thing? How would Reagan have navigated the Cold War if he’d had to deal with cyberterrorism? And how might the 2000s have been different if Florida had used digital voting machines instead of punch card ballots resulting in the infamous hanging chads?

The digital age has changed more than just the day-to-day lives of average voters. New and emerging technology has fundamentally changed facets of the race to the White House and the issues the new President will face. National security threats, election rigging, what constitutes modern-day scandals and public opinion influencers have all evolved into truly digital problems. As voters head to the polls today, let’s take a quick look back at some of the ways modern-day tech has made this a new kind of Presidential race—and what takeaways you can apply to customer engagements.

Trump & Social Media

The notion of the “October surprise,” which is a scandal that occurs just before an election and sways the electorate considerably, isn’t new. But social media and the internet played a particularly big part in the 2016 election.

On October 7, footage from a 2005 conversation between Donald Trump and TV commentator Billy Bush of Access Hollywood came to light. You’ve likely all heard the tape, so we’ll spare you the details here for the sake of both brevity and class. Within hours, the Twittersphere was on fire as users shared the video and offered their opinions on its content. By the next day, it was all many Facebook users were talking about. Soon after, the interwebs were riddled with memes. And all that social media wildfire had a significant impact on polling numbers. In Wisconsin alone, Hillary Clinton gained 20 points in the polls in the three days following the video’s leak.

In a rare but fascinating example of the type of techie conversations we have in the channel overlapping with the conversations most Americans have on their Facebook walls, a post from David Robinson of the blog Variance Explained back in August shed light on the intersection of politics, social media and data science. This one’s for all you data geeks out there. Using text mining and sentiment analysis, Robinson was able to tell which tweets came from the Trump campaign and which were posted by his staff.

“My analysis…concludes that the Android and iPhone tweets are clearly from different people, posting during different times of day and using hashtags, links, and retweets in distinct ways,” he wrote. “What’s more, we can see that the Android tweets are angrier and more negative, while the iPhone tweets tend to be benign announcements and pictures.” (All emphasis original.)

Robinson breaks down his analysis in the post, well worth a read for those fascinated by data analytics.

Hillary’s Curse: WikiLeaks

For her part, Clinton has been plagued by the existence of hackers and WikiLeaks, the website whose mission is to publish and comment on leaked documents alleging government and corporate misconduct, according to its website. Back in March, the site published a searchable archive for more than 30,000 emails sent to and from a private server Clinton used while Secretary of State.

Though an FBI investigation cleared her of any criminal wrongdoing, Clinton’s woes over archived emails on her staff’s devices resurfaced on October 28. FBI director James Comey sent a letter to Congress saying the agency was investigating an additional discovery of 650,000 emails, drawing Democratic wrath and Republican praise for commenting on an ongoing investigation just days before the general election.

Eight days later, the FBI once again cleared Clinton of wrongdoing, prompting Trump to say in a Michigan campaign speech that “you can’t review 650,000 emails in eight days.” Au contraire said Wired, laying out a series of steps that most IT managers will be familiar with. After all, in the digital age, it isn’t as though agents had to read each email manually.

What it comes down to is a pretty basic use of data analytics. By identifying emails by their message ID, a unique alphanumeric identifier, the FBI filtered out those that had been examined and cleared in the previous investigation. In case any slipped through the cracks, they could use forensics tools to make cryptographic “hashes” that convert portions of text into shorter character strings that a program can easily compare for duplicates. It’s similar to software programs that check for plagiarism, said Wired.

In his blog, cybersecurity consultant Rob Graham wrote that “computer geeks” could have gotten through the emails much faster than eight days. “Computer geeks have tools that make searching the emails extremely easy,” wrote Graham. “Given those emails, and a list of known email accounts from Hillary and associates, and a list of other search terms, it would take me only a few hours to reduce the workload from 650,000 emails to only a couple hundred, which a single person can read in less than a day.”

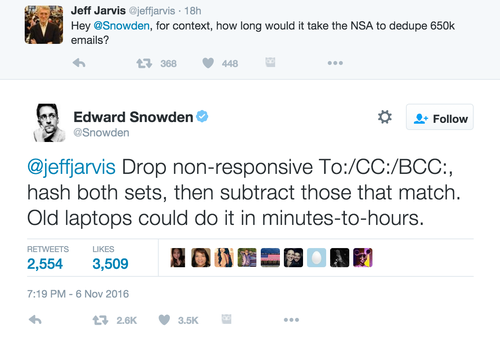

Even Edward Snowden weighed in.

Are voting booths rigged against Donald Trump?

One of the recurring complaints of the Trump campaign is that the election is rigged against him—the media, the polls and the voting booths are all designed in a way to ensure a Clinton victory. When it comes to tech, the most pertinent of these is the machines Americans use to vote.

In 2012, the Pew Center on the States released a report detailing the ways that America’s voting system is hopelessly antiquated. “Voter registration in the United States largely reflects its 19th-Century origins and has not kept pace with advancing technology and a mobile society.”

The report goes on to reveal several startling details, many of which have been repeated by the Trump campaign in their complaints of election rigging, namely:

Approximately 24 million—one of every eight—voter registrations in the United States are no longer valid or are significantly inaccurate

More than 1.8 million deceased individuals are listed as voters.

Approximately 2.75 million people have registrations in more than one state.

While the statistics are disconcerting, their impact is negligible, according to David Becker, the report’s co-author. “To commit voter fraud like this, someone would have to show their face before witnesses in order to cast a single ballot in an election where there might be 140 million ballots. It doesn’t make much sense to do that,” Becker told Politico. “It’s a felony with hardly any payoff. It’s not the crime of the century.”

Perhaps more troubling is the age of the voting machines many Americans are using. After the infamous Election of the Hanging Chads in 2000, the federal government passed the Help America Vote Act in 2002. The act distributed $2 billion for the states to invest in new voting technology—much of which is still in place today, 14 years later.

Last year, voting rights researchers Christopher Famighetti and Lawrence Norden co-authored “America’s Voting Machines at Risk” to examine the role that aging technology can play in dissuading voters from standing in long lines to cast their ballots.

“In 2016, for example, 43 states will use electronic voting machines that are at least 10 years old, perilously close to the end of most systems’ expected lifespan,” they wrote. “Old voting equipment increases the risk of failures and crashes — which can lead to long lines and lost votes on Election Day — and problems only get worse the longer we wait.”

Think about it this way: could your customers effectively run and grow their businesses on 10-year-old machines and systems?

Is Russia actively working to ensure a Trump victory?

In August, Russian hackers breached the private email accounts of more than 100 officials and groups affiliated with the Democratic National Committee. The attackers gained access to the fund-raising arm for House Democrats and a DNC voter analytics program in use by Clinton’s campaign. The leaked emails led Debbie Wasserman Schultz to resign as the DNC chairwoman after released emails revealed her bias toward Hillary Clinton over Senator Bernie Sanders.

Allegations that the Russians were trying to skew the election in favor of Donald Trump quickly began to fly, which weren’t helped by Trump’s comments that he hoped Russian intelligence had hacked Clinton’s personal email and urged them to publish whatever they found.

Last month, the White House stepped in and formally accused Russia of being behind the hack in an attempt to influence the election—and indirectly, the policies that the future President would put into place.

“Such activity is not new to Moscow—the Russians have used similar tactics and techniques across Europe and Eurasia, for example, to influence public opinion there,” read a statement from director of national intelligence, James Clapper Jr., and the Department of Homeland Security. “We believe, based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia’s senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.”

There are a couple of other hacking fears for Election Day itself. Some experts believe that Russia organized a recent attack on polling data in the Ukraine in an attempt to manipulate news outlets into calling incorrect victories before the polls closed. Ben Buchanan and Michael Sulmeyer noted in a Harvard Cyber Security Project report that investigations revealed “offenders were trying by means of previously installed software to fake election results.”

In addition, now that voter databases are digital instead of on paper, it’s much easier for hackers to wreak havoc on Election Day by making changes to identifying information, leading to long waits to cast a ballot.

After the election, national cybersecurity issues await

But all of this is small potatoes compared to what’s coming next. After all the campaigning has (thankfully) come to a close, the votes have been cast and we’ve sent a new Commander-in-Chief to the White House, our new President and Congress is going to have to grapple with issues the likes of which we’ve never dealt with on both foreign on domestic fronts.

The VAR Guy has written on the cyberthreats from other nation-states that the new administration will have to decide how to handle. From Russia to North Korea, this election cycle has been riddled with accusations of meddling.

But the issue is much broader and more nuanced than that, touching many different state department policy fronts. With the advent of cloud technology, the cyber-borders between countries are less clear. Who has rights to American data housed in other countries? When a hack like the recent one on Dyn has ties to equipment made in China or elsewhere, how will trade deals be affected? Will individual governments be held accountable for attacks perpetrated by their citizens, and under what circumstances?

The Mirai botnet attack on internet infrastructure firm Dyn that knocked out internet access to many sites for much of the eastern United States should raise serious concerns about the resources allocated to American digital infrastructure. For example, while last week’s reports that the entire country of Liberia was knocked off the internet were exaggerated, it’s no longer beyond the realm of possibility that America’s critical infrastructure could be seriously compromised by technology released by foreign governments.

“Of course, cyber-attacks are far more than stealing information,” Jeff Williams, CTO at Contrast Security, told the VAR Guy. “The real concern is that a skilled adversary might interfere with the automated systems that our lives depend on in the U.S., such as food and water, energy, finance, transportation, government and defense–to name just a few.”

And protecting those assets isn’t something the government can do without partnering with the private sector, including the channel.

Neither candidate demonstrated a firm grasp on the cyberthreat from nation-states like Russia during the debates, and security experts operating within the channel were vocal about their unpreparedness.

“What both candidates underscored in their response was a lack of knowledge and understanding when it comes to the cyberlandscape,” Ladar Levison, founder of encrypted email service Lavabit, told the VAR Guy. “Neither offered any concrete plans for the defense of this country or its infrastructure. At best they simply boasted about their willingness to engage in cyberwarfare, with nothing but blind hope for those who worry about it escalating into a hot war.”

Privacy vs. security: the new domestic agenda

When the FBI demanded that Apple unlock a phone belonging to one of the shooters in the San Bernadino shooting, it started a national debate about how much jurisdiction federal agencies have over users’ private data.

In addition, companies are protesting the court-imposed gag orders that keep providers from informing customers of investigations into user data on the grounds that they violate the Bill of Rights. Back in April, Microsoft sued the Justice Department over the practice, arguing the gag orders violate the Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches or seizures of private data, as well its First Amendment right to speak to its customers.

The second decade of the 21st century has produced an ever-increasing number of conflicts between the DOJ and private technology companies. In 2013, Levison’s company Lavabit decided to shut down operations rather than comply with a court order to turn over Edward Snowden’s user data. Last month, the Justice Department issued a subpoena to the maker of encryption app Signal, Open Whisper Systems, demanding subscriber details such as addresses, telephone numbers, email addresses and payment methods. Further, they wanted information on IP addresses and browsers that may have been used by account holders. And just last week, reports surfaced that Yahoo! built a system to scan user emails under orders from US intelligence agencies.

In perhaps the most blatant example of how behind the legal times the US is to address such questions, remember that the law at the heart of the debate is 227 years old. There’s a single line in the All Writs Act of 1789 that says, “The Supreme Court and all courts established by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.”

You can bet your bottom dollar that updating such statutes to be applicable to the digital age will be one of the many issues facing the federal government in 2017.

It’s a brave new world

If George W. Bush was the “Internet President,” and Barack Obama was the “Social Media President,” it’s looking like our 45th Commander-in-Chief will be the “Cloud President.” From clarifying American citizens’ rights in a digital age to defining national cybersecurity, the State Department has some serious challenges in front of it. The federal budget will have to be rethought in order to include the upgrade of legacy systems and hardware to protect critical infrastructure and keep up with digital technology. And everyone’s going to need to be more cognizant of the information they put out via the internet, whether top-security emails or social media posts.

We’ve rarely if ever seen a presidential election like this one, but it’s nothing compared to the debates and governmental shifts we’ll see starting January 20.

About the Author

You May Also Like